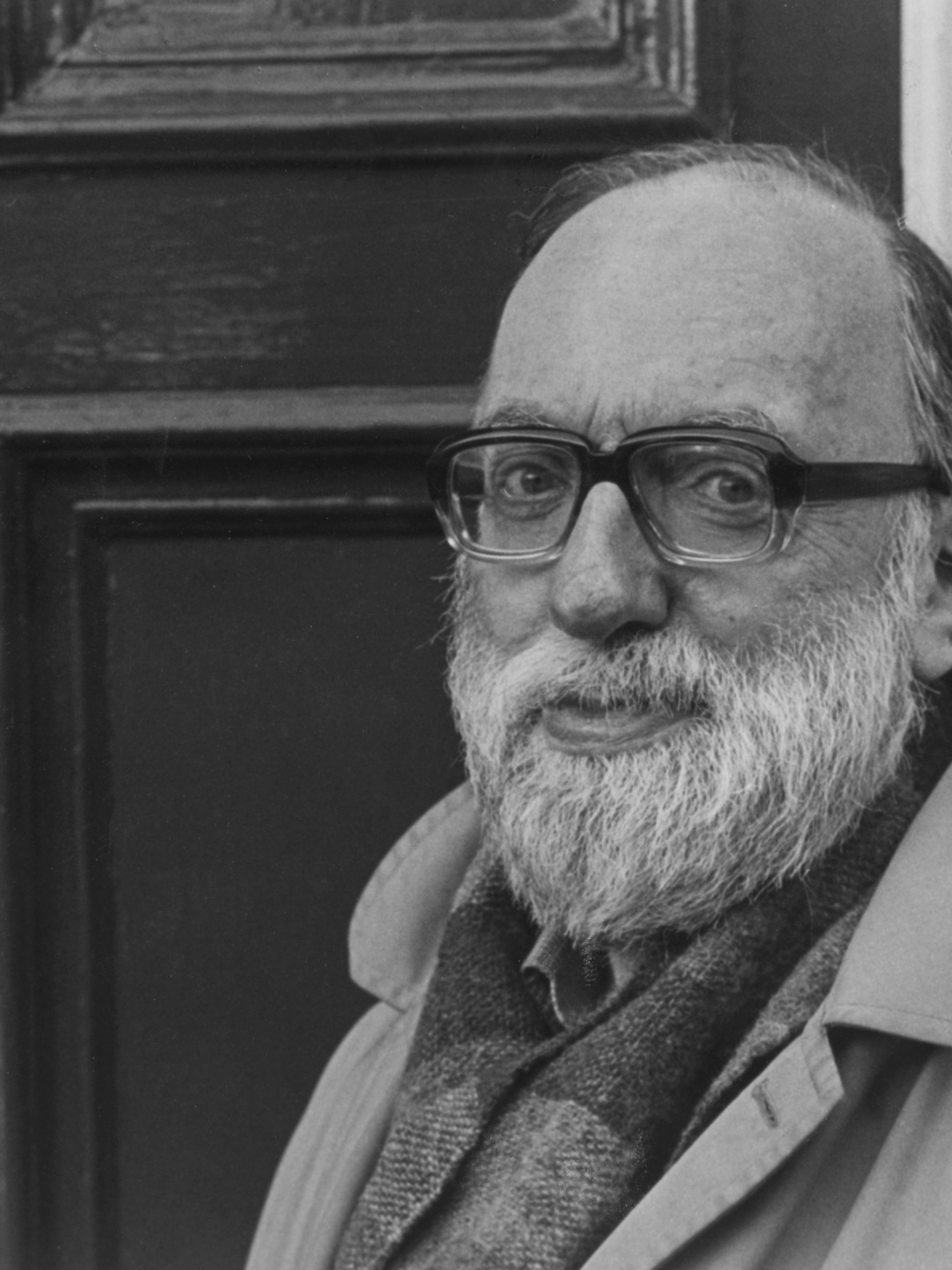

Michael Krüger was born in Wittgendorf, Germany, in 1943, and spent his youth and college years in West Berlin. He now lives in Munich, running the Carl Hanser publishing house. He and Klaus Wagenbach, in 1968, founded the literary annual Tintenfisch. He is editor of the periodical Akzente, the first outlet for a great many promising authors. His first collected poems, Reginapoly, appeared in 1976, and he has continued publishing ever since. His work has been translated into many languages.

The pomes published here first appear in English translation in Sirena: Poetry, Art, and Criticism 2009:2 (Johns Hopkins UP), edited by Jorge R. G. Sagastume, the editor of The Pasticheur. All translation into English were done by Eva Bourke.

Marx redet

Manchmal, wenn es im Westen aufklärt,

schaue ich den glitzernden Geldflüssen zu,

die schäumend über die Ufer treten

und das eben noch dürre Land überschwemmen.

Mich amüsiert die Diktatur des Geschwätzes,

die sich als Theorie der Gesellschaft

bezahlt macht, wenn ich den Nachrichten

von unten glauben darf. Mir geht es gut.

Manchmal sehe ich Gott. Gut erholt sieht er aus.

Wir sprechen, nicht ohne Witz und dialektisch

erstaunlich versiert, über metaphysische Fragen.

Kürzlich fragte er mich nach der Ausgabe

meiner Gesammelten Werke, weil er sie

angeblich nirgendwo auftreiben konnte.

Nicht dass ich daran glauben will, sagte er,

aber es kann ja nichts schaden.

Ich gab ihm mein Handexemplar, das letzte

der blauen Ausgabe, samt Kommentaren.

Übrigens ist er gebildeter, als ich dachte,

Theologie ödet ihn an, der Dekonstruktion

streut er Sand ins Getriebe, Psychoanalyse

hält er für Unsinn und nimmt sie nicht

in den Mund. Erstaunlich sind seine Vorurteile.

Nietzsche zum Beispiel verzeiht er jede

noch so törichte Wendung, Hegel dagegen

kann er nicht leiden. Von seinem Projekt

spricht er aus Schüchternheit nie. Bitte,

sagte er kürzlich nach einem langen Blick

auf die Erde, bitte halten Sie sich bereit.

Marx Speaks

Sometimes when it clears up in the west

I watch the glittering streams of money

foam and rise over their banks

and flood the hitherto parched land.

I am amused by the dictatorship of blather

which pays off as a theory of society

if I can believe the news from below. I am well.

Sometimes I see God. He looks relaxed.

We talk about metaphysical questions,

not without humor and surprisingly

well-versed in dialectics.

Recently he asked me for the edition

of my Collected Works because, he claimed,

he couldn’t find them anywhere.

It’s not that I want to believe in it, he said,

nevertheless it can’t do any harm.

I gave him my personal copy,

the last of the blue edition, plus commentaries.

Actually he is more well-read than I had thought,

theology bores him, he throws a spanner

into the works of deconstruction,

psychoanalysis is nonsense, he thinks

and won’t entertain it. His prejudices are amazing.

For example he forgives Nietzsche even

his most foolish phrases, Hegel, on the other hand

he can’t stand. Due to his shyness

he never talks about his project. Please,

he said recently, after a long look

at the earth, please be prepared.

Geschichte der Malerei

Ich las eine Geschichte der Malerei

von den Anfängen bis heute.

Eine Geschichte der weißen Lämmer,

bevor sie der Strahl trifft.

Eine Geschichte der kleinen, geflügelten Engel

und des jungfräulichen Rasens,

von Gänseblümchen übersät.

Eine Geschichte der Stoffe

und der Durchsetzung des Goldes.

Eine Geschichte der feinsten Tränen

auf blassen Gesichtern.

Eine Geschichte der gewölbten Stirnen

und der eingefallenen Wangen.

Eine Geschichte des Wassers

und wie man es malt.

Eine Geschichte der Schulen,

der Stile, des Kampfes um Wahrheit.

Eine Geschichte der Gewalt,

der Tücke und Gemeinheit,

der Treulosigkeit und des Verrats,

der gebrochenen Eide, der Revolten

und der nie aufhörenden Schlächtereien.

In den Fußnoten las ich auch

eine Geschichte der Scham,

eine verwickelte Geschichte des Trostes.

Insgesamt eine schöne Geschichte,

die Geschichte der Malerei,

und nicht nur für die Augen.

In seinem Nachwort erklärt der Autor

umständlich, was wir sähen, sei

nur Farbe in verschiedenem Auftrag.

Er hatte das Gift vergessen,

das ihr beigemengt war,

das Gift für die Augen.

A history of painting

I read a history of painting

from the beginnings until today.

A history of white lambs

before the ray strikes them.

A history of small winged angels

and the virginal lawn

strewn with daisies.

A history of fabrics

and the assertiveness of gold.

A history of the most delicate tears

on pale faces.

A history of rounded foreheads

and hollow cheeks.

A history of water

and how to paint it.

A history of schools, styles,

of the battle for truth.

A history of violence,

of treachery and spite,

of disloyalty and betrayal,

of broken oaths, of uprisings

and never-ending slaughters.

In the footnotes I also read

a history of shame,

a complex history of consolation.

All in all a beautiful history,

the history of painting

and not only for the eyes.

In his epilogue the author explained

ponderously that what we saw

was merely colour performing different tasks.

He had forgotten the poison

that was mixed with it,

the poison for the eyes.